WordPress Hacking 101: A Comprehensive Security Assessment Guide

WordPress powers a huge portion of the internet, and that popularity comes with a predictable reality: it gets attacked constantly. What makes WordPress especially interesting from an offensive security perspective is its modular design. The core CMS might be reasonably hardened, but themes, plugins, misconfigurations, and leftover files often expand the attack surface far beyond what most site owners expect.

This guide walks through a practical, structured workflow for WordPress testing, starting with passive fingerprinting and moving through enumeration, vulnerability research, exploitation paths, and remediation. The focus is not just “which tools to run,” but why each step matters and how to validate findings when automation fails.

Introduction: Understanding the Target Landscape

A WordPress target is rarely “just WordPress.”

A real-world WordPress deployment typically includes:

- A WordPress core version (sometimes hidden, sometimes leaking).

- A set of plugins (often the most vulnerable component).

- A theme (sometimes custom, sometimes outdated).

- A web server layer (Apache, Nginx, caching, CDNs, WAFs).

- Extra files created by developers, backup plugins, or staging workflows.

The main objective during WordPress testing is to build a reliable map of what is installed and exposed:

- Which version of WordPress core is running.

- Which plugins/themes exist and their versions.

- Which users exist (for brute forcing or targeted attacks).

- Which endpoints expose sensitive functionality (password reset flows, XML-RPC, REST API).

- Which files leak secrets or allow escalation (configs, backups, logs, git folders).

Once you can confidently answer those questions, exploitation becomes far less guesswork and far more mechanical.

Phase 1: Passive Reconnaissance (Fingerprinting)

Before sending aggressive requests, it is worth confirming the technology stack quietly. Passive recon reduces noise and helps avoid triggering rate limits, WAF rules, or alerting.

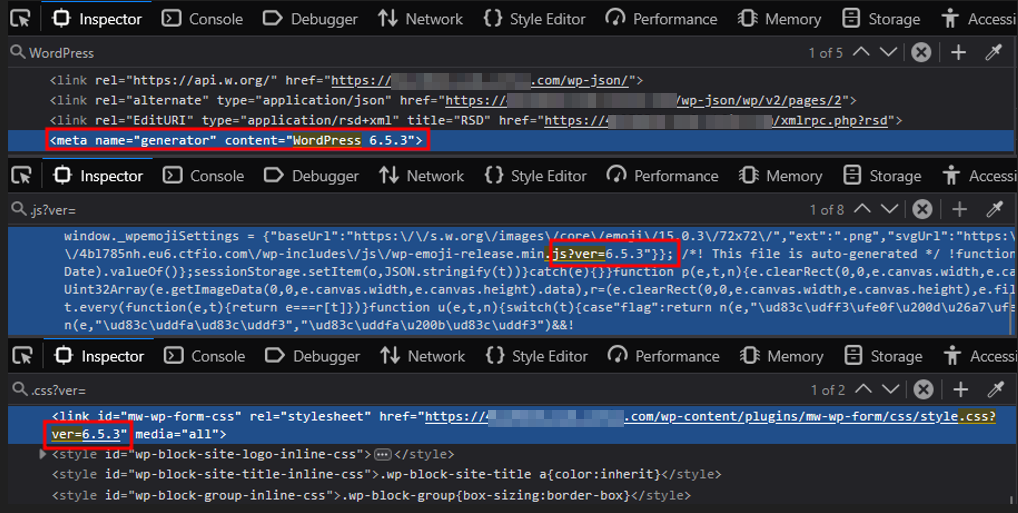

Source code analysis (the “F12 check”)

Start with what the site already gives you.

Open Developer Tools (F12) or view source (Ctrl+U) and look for indicators such as:

- The

wp-content/path, which strongly suggests WordPress. - Generator tags like:

<meta name="generator" content="WordPress 5.x" /> - Version strings in scripts and styles:

.js?verand.css?ver

Even if the generator tag is removed, plugins and themes frequently leak the WordPress version through their assets. This is an important detail: many teams focus on hiding the obvious marker but overlook the indirect ones.

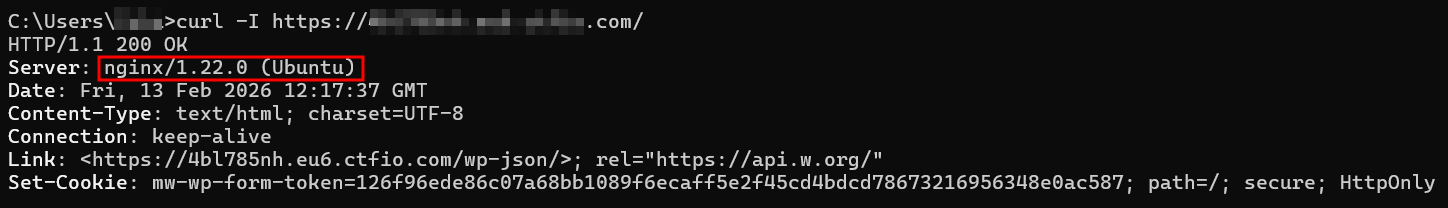

Banner grabbing (server exposure)

Server headers can hint at infrastructure weaknesses, outdated services, or misconfigurations.

A quick HEAD request is often enough:

curl -I <https://target.com>

Pay attention to:

Server(Nginx/Apache versions can sometimes be exposed)X-Powered-By(may reveal PHP or other backend frameworks)

This does not guarantee a vulnerability, but it helps you build context. If the server layer is leaking version info, it is often a sign the rest of the stack is not carefully hardened either.

Phase 2: Active Enumeration and Reconnaissance

Once you have confirmed WordPress, move to structured enumeration. The goal is to inventory what is installed and exposed.

Automated Vulnerability Scanning with WPScan

WPScan is typically the first active tool to run because it covers a lot quickly.

Performing an Initial Security Scan

Start with a basic scan to get a general picture:

wpscan --url <https://target.com/> --random-user-agentUsing a random user agent is simple, but it helps reduce trivial blocking based on default WPScan signatures.

Aggressive plugin and theme detection

If passive or baseline enumeration misses plugins, move to aggressive detection:

wpscan --url <https://target.com> \\\\

--wp-content-dir /wp-content/ \\\\

--enumerate vt \\\\

--plugins-detection aggressive \\\\

--api-token <YOUR_TOKEN> \\\\

--random-user-agent

The API token matters because vulnerability data changes frequently. Without it, your scan output may be incomplete or outdated, which can lead to false confidence.

Manual enumeration (when tools are blocked)

Automated tools are useful, but they are not “truth.” Many environments block scanners, rewrite responses, or serve different content based on behavior.

Manual checks help confirm what exists.

Plugin version checks

If you identify a plugin name (for example, mw-wp-form), try to confirm the exact version through plugin files such as:

/wp-content/plugins/mw-wp-form/readme.txt

Why this works: plugin readmes often remain accessible and include version details that are enough for vulnerability matching and exploit research.

Core confirmation files

Common WordPress files sometimes remain exposed:

/readme.html/license.txt

If accessible, they can confirm WordPress core presence and sometimes version range.

Enumerating WordPress Users and Accounts

If you plan credential attacks, the hardest part is often not passwords, but valid usernames.

Technique 1: Author archives

Try: /?author=1 , /?author=2

If the response redirects to something like /author/admin/, you likely discovered a valid username.

Technique 2: REST API exposure

Check:

/wp-json/wp/v2/users

In many WordPress setups, this endpoint returns a user list including slugs. If you get usernames here, it significantly reduces brute force uncertainty.

Phase 3: Vulnerability Analysis and Assessment

After enumeration, you should have:

- A WordPress version (or a range)

- Plugin and theme names, ideally with versions

- Usernames or user identifiers

Now the task becomes: match your findings to known vulnerabilities and determine feasibility.

Identifying Public Exploits using Searchsploit

Searchsploit is an effective first stop for public exploits:

searchsploit wordpress <plugin_name>

searchsploit wordpress 5.x

This helps you quickly identify whether your target version has known issues. However, always validate exploit applicability. Many exploits require specific configuration states or plugin settings.

Common WordPress Vulnerabilities and Attack Vectors

XML-RPC (/xmlrpc.php)

If enabled, XML-RPC can support:

- Brute force amplification (multiple login attempts in a single request)

- Pingback-based abuse (sometimes leveraged for DDoS-like behavior)

Even if you are not planning DDoS testing, XML-RPC presence is important because it can increase brute force efficiency and reduce visibility.

Debug artifacts and improper error handling

A particularly valuable target:

/wp-content/debug.log

When WP_DEBUG_LOG is enabled, logs may expose:

- Full file paths (useful for LFI chaining)

- Database queries

- Plugin errors that reveal internal logic or sensitive data

Phase 4: Exploitation and Injection Paths

This phase is where controlled attacks begin. At this point you should be operating with a strong hypothesis, not random payload spraying.

Host header injection (password reset poisoning)

One impactful and often misunderstood issue in WordPress environments is Host Header Injection during password reset flows.

Some WordPress setups build password reset links using server variables derived from the Host header, such as $_SERVER['SERVER_NAME']. If the application trusts this header without validation, an attacker can influence where reset links point.

Result and impact

If successful, the victim receives a password reset link pointing to the attacker domain. If the victim clicks it, the reset token can be exposed to the attacker, leading to account takeover.

This is especially dangerous because it turns a legitimate security feature (password reset) into a delivery mechanism for compromise.

Executing Targeted Brute Force Attacks

Brute forcing should not be step one. It becomes reasonable only when:

- You have confirmed valid usernames.

- The login endpoints are reachable.

- XML-RPC or wp-login behavior indicates brute forcing is feasible.

Example WPScan brute force usage:

wpscan --url <https://target.com> \\\\

--usernames admin \\\\

--passwords /path/to/rockyou.txt

Rate limiting, lockout plugins, WAF rules, and logging are common. Validate defensively and keep tests controlled.

Phase 5: Sensitive File Discovery and Fuzzing

Even hardened WordPress sites fail due to exposed files created by human workflows: backups, logs, deployment artifacts, and forgotten setup scripts.

Critical Endpoints for Security Assessment

A practical hit list includes:

/wp-config.php(direct access is often blocked, but backups may not be)/wp-config.php.bak/[wp-config.php.save](<http://wp-config.php.save>)/wp-admin/install.php/wp-admin/setup-config.php/wp-admin/upgrade.php/wp-links-opml.php/wp-mail.php/backup/

Directory fuzzing with ffuf

Example:

ffuf -u <https://target.com/FUZZ> \\\\

-w /path/to/wordlist.txt \\\\

-e .php,.bak,.zip

The goal is not to scan everything. The goal is to discover high-impact mistakes quickly: config backups, SQL exports, zip archives, and writable upload paths.

Advanced sensitive file hunting

Hidden log files

Logs can contain credentials, tokens, PII, or internal paths. Common locations include:

/wp-content/debug.log/wp-content/uploads/wc-logs/(WooCommerce logs)/wp-content/uploads/wp-activity-log//wp-content/plugins/updraftplus/(backup-related logs)

Environment and config leaks

Modern setups sometimes expose:

/.env/wp-config.php.oldand similar variants/.git/HEAD(critical if accessible, as it can lead to full source disclosure)

Google dorking

Search engines can do passive discovery for you. Example patterns:

- Exposed logs:

site:[target.com](<http://target.com>) inurl:wp-content ext:log

- Database exports:

site:[target.com](<http://target.com>) "index of" inurl:wp-content ext:sql

- Config backups:

site:[target.com](<http://target.com>) inurl:wp-config ext:txt OR ext:bak

- User leaks:

site:[target.com](<http://target.com>) inurl:/wp-json/wp/v2/users

- Setup scripts:

site:[target.com](<http://target.com>) inurl:wp-admin/setup-config.php

This approach is often underused, but it can uncover leaks without actively probing the application.

High-value plugin files and AJAX endpoints

Two categories matter:

- Version sources:

/wp-content/plugins/[PLUGIN]/readme.txt/wp-content/plugins/[PLUGIN]/changelog.txt

- AJAX endpoint:

/wp-admin/admin-ajax.php

admin-ajax.php is frequently a goldmine because plugins expose actions through it. If input validation is weak, it can become an entry point for data exposure, unauthorized actions, or injection.

Phase 6: Exploitation and Verification

Once you locate a plausible vulnerability, the difference between a good tester and an unreliable one is verification discipline. You want to confirm impact with the smallest effective payload.

Arbitrary file upload (often leads to RCE)

File upload vulnerabilities are common in plugins that accept user uploads (forms, galleries, profile images).

Developers often validate only:

- File extension

- Content-Type header

Both can be bypassed.

Minimal verification workflow

- Payload: Save

<?php system($_GET['cmd']); ?>asshell.phtmlorshell.php.pngto bypass filters. - Upload: Submit the file via the vulnerable plugin form.

- Verify: Access the file URL with

?cmd=id. If the response showsuid=33(www-data), you have confirmed RCE.

Local file inclusion (LFI)

Some plugins use user-controlled input in functions such as include() or file_get_contents().

Example payload structure:

<https://target.com/wp-content/plugins/vuln-plugin/index.php?page=../../../../wp-config.php>

WordPress often blocks direct HTTP access to wp-config.php, but LFI bypasses that restriction because the server reads the file locally.

SQL injection (SQLi)

SQL injection often appears in custom or poorly maintained plugins.

A quick indicator test

Add a single quote to parameters:

?id=1'

If errors appear like “You have an error in your SQL syntax,” you may have a viable injection point.

Remediation

A good report does not stop at exploitation. It explains how to prevent recurrence.

- Fix Host Header: Validate the

Hostheader at the web server level (Apache/Nginx) or use an application-level allowlist. - Disable XML-RPC: Turn this off if unused to prevent brute force amplification and DDoS attacks.

- Reduce Leaks: Remove generator meta tags,

readme.html, and?ver=strings to minimize reconnaissance data. - Block Enumeration: Restrict access to

/wp-json/wp/v2/usersand/?author=*to hide usernames. - Layered Defense: specific WAF rules can block automated scanners, but combine them with rate limiting and strong authentication for real security.

Conclusion

Securing WordPress requires looking beyond the core CMS to its vast, often insecure plugin ecosystem. By rigorously enumerating user roles and validating configuration flaws like exposed debug logs, we expose the true attack surface.

Effective pentesting isn't just about running WPScan; it's about understanding how WordPress's modular architecture handles data and where it breaks down.

How Jsmon Can Help

While WPScan focuses on server headers and known vulnerabilities, Jsmon digs into the client-side code where developers often leave massive clues.

- Uncover Hidden Plugins: Finds plugins via their JavaScript files, effectively bypassing security headers that hide version numbers.

- Expose Custom Endpoints: Scans JS bundles to map undocumented REST API routes and AJAX parameters often missed by wordlists.

- Find Hardcoded Secrets: Instantly detects API keys (AWS, Stripe) buried in custom theme files, securing critical findings without brute-forcing.