Race Conditions Explained: From TOCTOU to Business Logic Bypasses

A comprehensive guide on how to find, exploit, and prevent race condition or concurrency attacks in modern web applications.

Race conditions are one of those vulnerability classes that feel almost “too simple” until you see the impact. At the core, the bug is not about a fancy payload or an obscure bypass. It is about timing.

A race condition happens when an application behaves correctly for a single request, but breaks when two or more requests hit the same shared state at nearly the same time. If the system checks a condition and then uses that result a moment later, an attacker tries to squeeze another request into that tiny window.

In this article, we will build a clear mental model of race conditions, starting from classic OS TOCTOU bugs and moving into modern web exploitation, including HTTP/2 single-packet attacks and practical hunting patterns.

Introduction

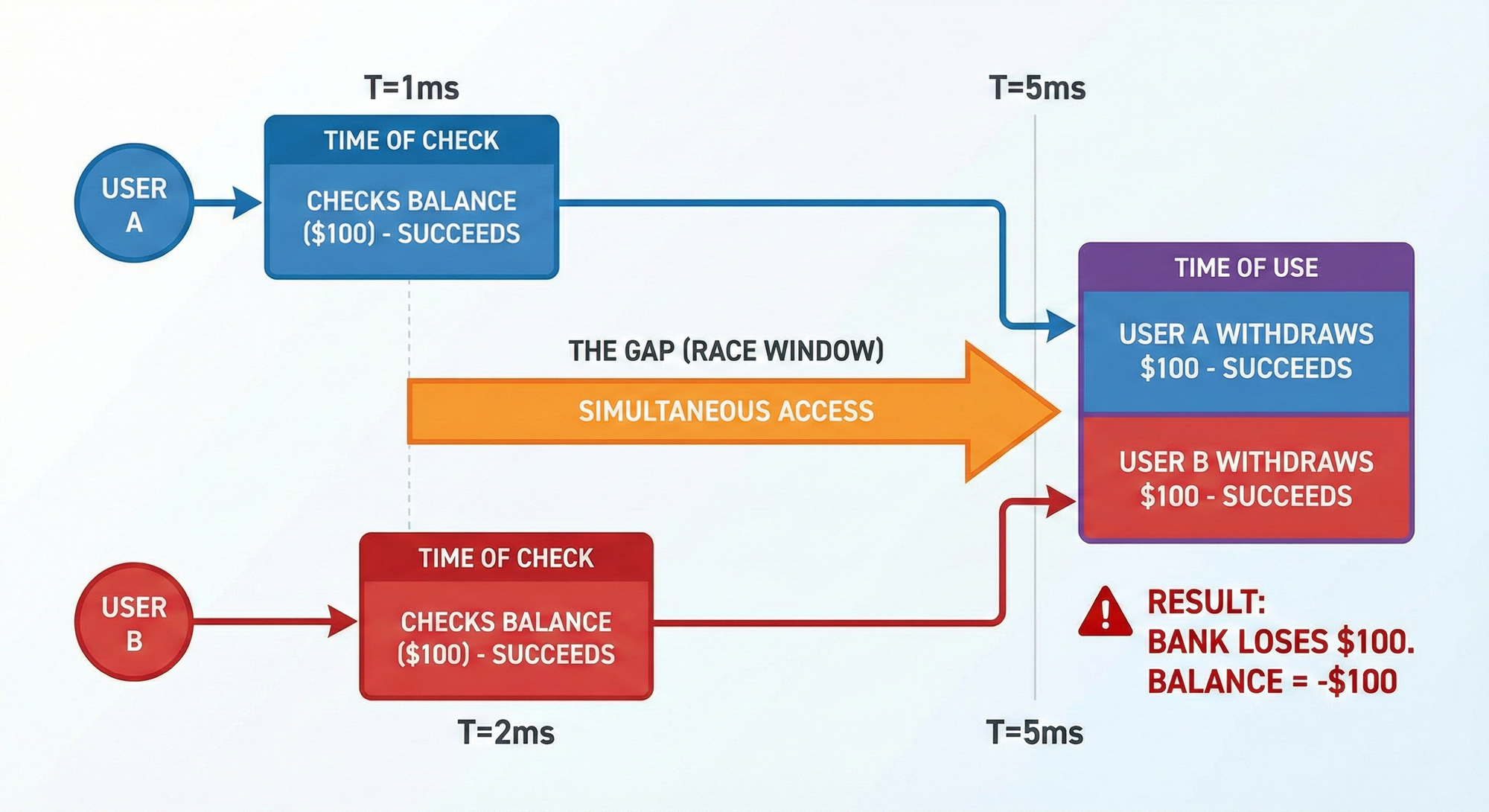

Imagine two people at two different ATMs. They share a joint account with exactly $100. At the exact same moment, both press “Withdraw $100.”

In an ideal system, one withdrawal would succeed, the balance would become $0, and the second withdrawal would fail. But real systems do not execute all logic atomically. There is often a small gap between:

- Time of Check: “Is there enough balance?”

- Time of Use: “Deduct balance and dispense cash.”

If both withdrawals pass the check before either updates the balance, the bank just paid out $200 from a $100 account.

That is the essence of a race condition: two operations collide on the same shared resource, and the application loses control of state.

Understanding TOCTOU Vulnerabilities

Race conditions did not start in web apps. Many of the earliest real-world exploits were operating system issues, especially around file permissions and filesystem operations.

What is TOCTOU?

TOCTOU stands for Time-of-Check to Time-of-Use.

A TOCTOU bug exists when a program checks a property of a resource (ownership, permissions, existence), then later uses that same resource assuming nothing changed. In the gap between the two actions, an attacker changes what the program is actually pointing at.

Example Scenario: Local Privilege Escalation via Temporary Files

Consider a script running as root that writes to a file in /tmp, but only if the file is “owned by the calling user.”

A simplified flow looks like this:

- Check: the program calls something like

stat(file)to confirm ownership. - The gap: the program does other work, or simply gets scheduled out for a moment.

- Use: the program calls

open(file)and writes privileged data.

If an attacker can swap the file between step 1 and step 3, the script may end up writing to a protected target.

How to Exploit File System Race Conditions

Historically, attackers tried to swap the file using slower tools like mv or repeated symlink changes. On busy systems, this was unreliable.

A more reliable modern technique is to exploit atomic filesystem operations. One commonly referenced approach uses the Linux renameat2 system call with RENAME_EXCHANGE, which performs an atomic swap of two filesystem entries.

// Illustrative technique: rapid atomic swaps to “strobe” file state

// until the vulnerable program hits the unsafe window.

while (1) {

syscall(SYS_renameat2,

AT_FDCWD, argv[1],

AT_FDCWD, argv[2],

RENAME_EXCHANGE);

}The important concept is not the specific syscall. The concept is that the attacker tries to make the state flip quickly enough that the privileged process eventually acts on the wrong object.

Web Application Race Conditions

Web apps have different primitives than operating systems, but the underlying failure mode is the same: a shared state is read, then modified later, without reliable serialization.

Common web “shared state” targets include:

- Account balance and wallets

- Inventory counts

- “One-time” promo codes and vouchers

- Rate-limiting counters

- Email change and identity verification workflows

- Multi-step checkout logic

Why Race Conditions Occur in Web Applications

Modern systems are intentionally concurrent:

- Multi-threaded web servers

- Distributed services

- Shared caches

- Asynchronous job queues

- Databases under load

All of that improves performance, but it also creates more opportunities for “check-then-use” logic to be split across time.

Race Condition Testing Methodology

Hunting race conditions on the web should not rely on luck. A reliable workflow is:

1) Predict: Identifying Potential Race Conditions

Look for workflows with collision potential:

- Limits and quotas

- “Use coupon once”

- “Maximum withdrawal per day”

- “One vote per user”

- State changes

- Anything that updates counters, inventory, balances, or flags

- Multi-step logic

- Add to cart → validate total → pay

- Change email → send verification → confirm

If you can point to a value that must be consistent, you can often frame a race hypothesis.

2) Probe: Detecting Race Conditions

Send small groups of requests and watch for evidence that the backend is not properly serializing:

- Response times that spike inconsistently

- Occasional duplicate successes when only one should succeed

- “Already used” checks that appear flaky

- Non-deterministic outcomes across repeated tests

3) Prove: Confirming Race Condition Vulnerabilities

Once you suspect a bug, the goal is to remove “internet randomness” from the equation and deliver requests as simultaneously as possible.

This is where modern tooling becomes decisive.

Best Tools for Race Condition Testing

Challenges in Exploiting Race Conditions

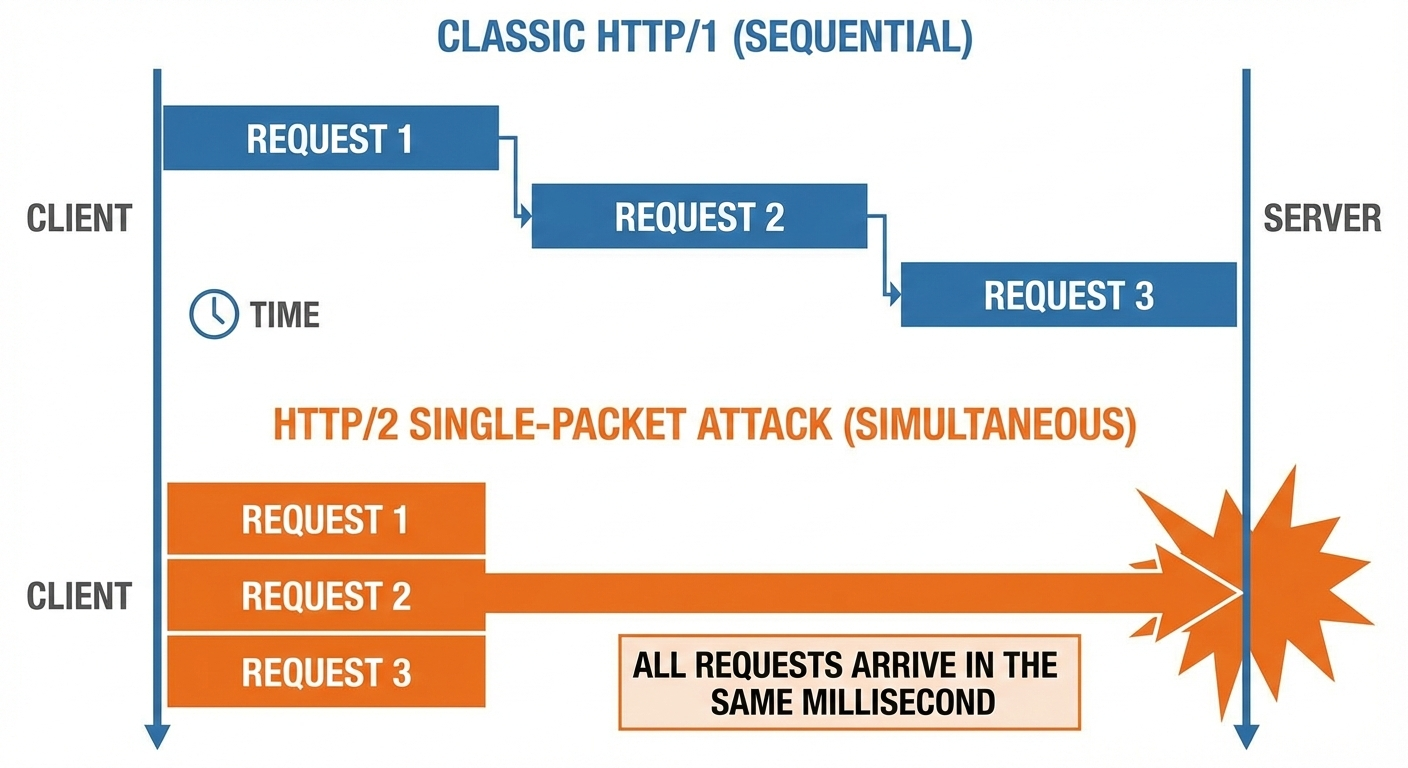

Even if you click “Send” twice quickly, request timing over the internet is noisy. One packet arrives a few milliseconds later simply due to routing, TCP behavior, and congestion.

For a long time, that jitter made web race condition testing inconsistent.

HTTP/2 Single-Packet Attacks Explained

With HTTP/2, multiple requests can be multiplexed over a single connection.

The key idea behind a “single-packet” style attack is:

- Prepare many requests.

- Send almost all of each request.

- Hold the final byte.

- Release the final byte for all requests at once.

That way, the server receives multiple complete requests at virtually the same time, which makes collisions far more repeatable.

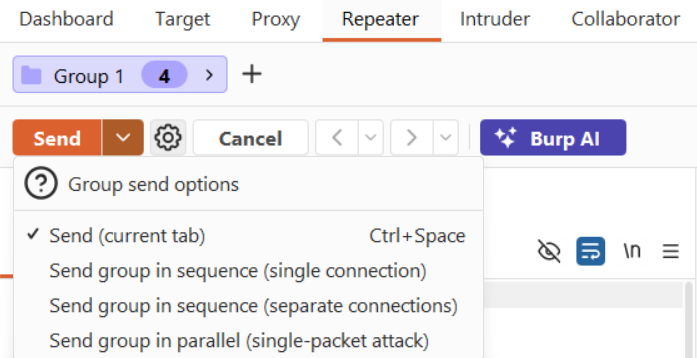

Burp Suite Repeater: Group Send Options

Burp Repeater provides multiple ways to send grouped requests. The differences matter:

Send group in sequence (separate connections)

- Behavior: new connection per request.

- Best for: baseline validation and “normal behavior” confirmation.

Send group in sequence (single connection)

- Behavior: faster, still sequential.

- Best for: speed when HTTP/2 is not available.

Send group in parallel (single-packet attack)

- Behavior: synchronized delivery using HTTP/2.

- Best for: race condition exploitation, especially limit overruns.

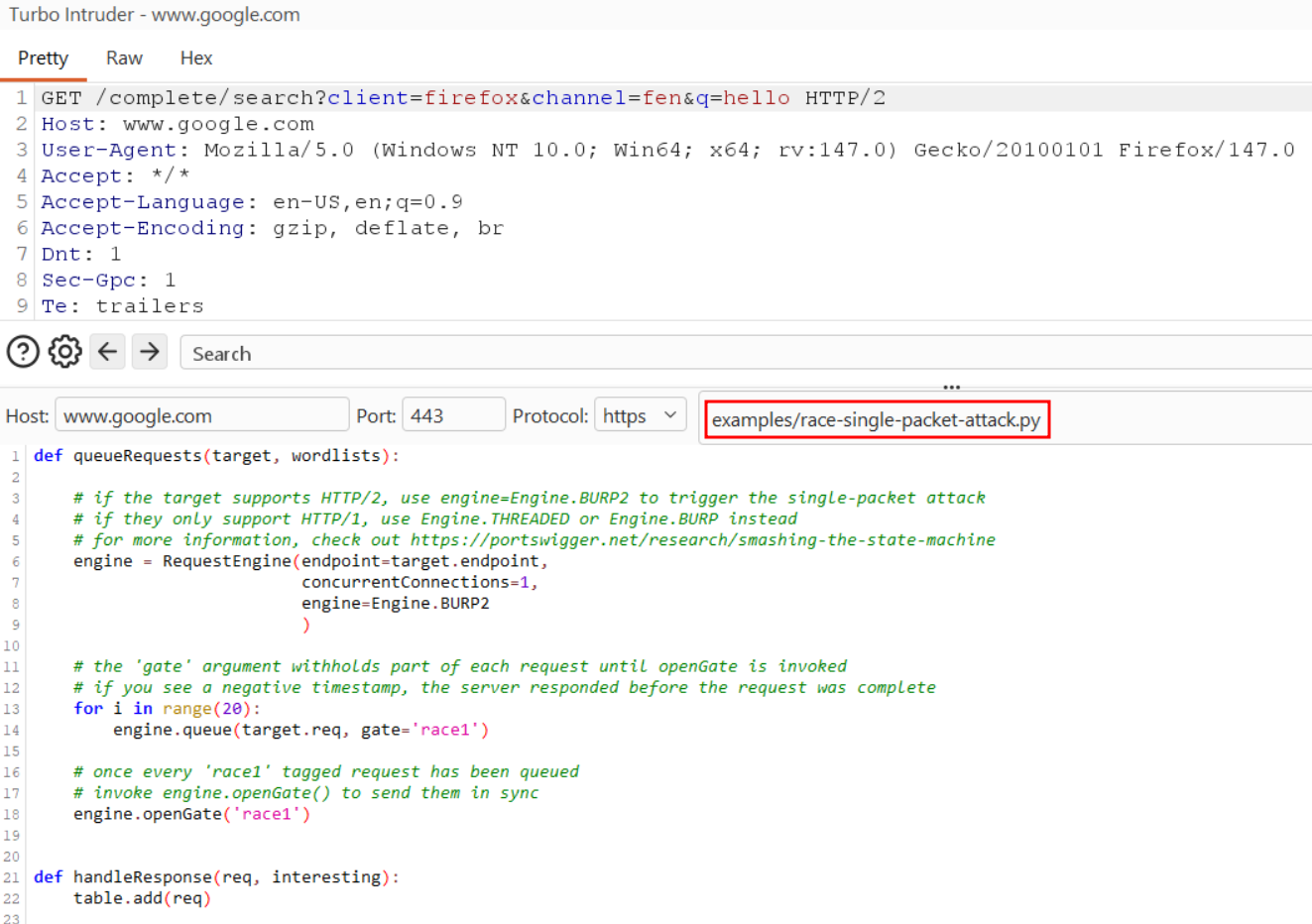

Turbo Intruder:

Burp Repeater is great for small batches, but race condition testing often needs:

- higher volume

- more control over timing

- custom logic across many requests

Turbo Intruder is built for that. A common workflow is:

- Send the target request to Turbo Intruder.

- Use the

race-single-packet.pytemplate. - Tune the run:

concurrentConnections(often 1)requestsPerConnection(for example 20 or 50)

- Execute and measure outcomes.

Types of Race Condition Attacks

1) Limit Overrun Vulnerabilities

Context: e-commerce, banking, coupons, reward points, gift cards.

The vulnerable pattern is usually “read-modify-write” split across time:

if (balance >= price) {

// [GAP] multiple requests can pass the check here

balance = balance - price;

give_item();

}If 20 requests hit the check before the first request updates the balance, you may spend 20 times what you actually have.

2) Bypassing Rate Limits

Rate limits are often enforced using counters in a cache or database.

If the system reads “attempts = 0” for many requests before incrementing the counter, you can exceed the intended limit.

Common targets include:

- OTP verification

- login brute forcing

- gift card redemption

- password reset endpoints

3) Multi-Endpoint Race Conditions

Not every race is “same endpoint, many times.” Some of the best bugs involve two different workflows sharing a single state.

Example idea:

- Request A: checkout validates cart total = $50

- Request B: add $500 item to cart

If the timing is right, validation happens on the cheap cart, but the expensive item is present when the order is finalized.

4) Single-Endpoint Races

Collisions within one action can still break logic.

Example: sending two “Change Email” requests simultaneously. Depending on how verification tokens are bound, confirming one email might unexpectedly confirm the other.

5) Partial Construction Race Conditions

This happens when an object exists “just enough” to be referenced, but not enough to be fully secured.

Example:

- Request A: create user record

- Request B: trigger password reset

If Request B lands before security flags are initialized (for example email_verified = false), default behavior can become dangerous.

6) Time-Sensitive Boundary Attacks

Some workflows depend on timestamps and expiration boundaries.

If a token “expires at 12:00:00,” racing multiple submissions at the boundary might allow repeated use before the database marks the token as expired.

How to Prevent Race Conditions

You cannot fix race conditions by “making code faster.” You fix them by enforcing correctness under concurrency.

1) Pessimistic Locking

Use transactional row locking such as:

SELECT ... FOR UPDATE

This forces other transactions to wait until the critical section completes.

2) Atomic Database Operations

Avoid the risky “read in application, then write later” pattern.

- Risky:

balance = balance - 10(application code) - Better:

UPDATE users SET balance = balance - 10 WHERE balance >= 10(single atomic SQL statement)

The atomic update ensures the check and modification happen as one operation.

3) Application-Level Locks (Mutexes / Semaphores)

When database-level locking is not enough or not applicable, use application locks to serialize critical actions per user or per resource.

This is especially useful for:

- wallet operations

- coupon redemption

- inventory reservation

How Jsmon Helps in Real Assessments

In many real engagements, exploitation is not the hard part. The hard part is finding the right endpoint and understanding what parameters the backend expects.

Discover Hidden or Undocumented Functionality

Jsmon can extract endpoints from JavaScript bundles, including:

- unreleased features

- versioned APIs

- internal endpoints accidentally exposed to the client

Finding something like /api/v2/transfer early can give you a head start on testing high-impact flows.

Construct Valid Payloads Faster

Jsmon can help you identify expected JSON fields (for example promo_code, recipient_id, or workflow-specific tokens). That reduces guesswork and helps you build reliable Turbo Intruder scripts even when the API is not documented.

Spot Client-Side Logic That Hints at Server Weakness

When you see strong client-side validation (for example if (user.hasCoupon) ...), it can be a hint that the backend might be relying on client state.

That is not a guarantee of a race condition, but it is a strong reason to test whether server-side enforcement is truly atomic.

Conclusion

Race conditions have evolved from niche OS TOCTOU bugs into reliable, high-impact web vulnerabilities. With HTTP/2 multiplexing and single-packet techniques, testing is no longer “spray and pray.” You can create deterministic collisions and prove real business impact.

When you review a workflow that checks a limit or validates state, ask a simple question:

What happens if I do this 20 times at once?