GraphQL Penetration Testing: A Comprehensive Guide to Discovery and Exploitation

GraphQL has changed how modern applications ship APIs. Instead of calling multiple endpoints like you would in REST, a client can ask for exactly the data it wants in one request. That is great for performance and developer experience, but it also shifts a lot of power to the client.

From a security perspective, that shift matters. If a GraphQL server does not enforce limits on what can be queried and how expensive a query can become, attackers can turn “flexibility” into data exposure, access control bypasses, and denial of service. This guide walks through a structured approach to testing GraphQL security, covering discovery, introspection, batching attacks, the N+1 problem, depth bypasses, and real-world access control and CSRF scenarios, along with practical defenses.

Introduction

GraphQL differs from REST in one key way: REST exposes fixed endpoints with predefined responses, while GraphQL exposes a schema and lets the client define the response shape.

That capability introduces two security realities:

- Clients can influence server workload. A single request can trigger a huge amount of backend work if the server accepts deep or wide queries without checks.

- Clients can enumerate and explore the API surface. If misconfigured, GraphQL can unintentionally document internal fields, types, and relationships that were never meant to be public.

Before going deeper, here are a few terms you will see repeatedly:

- Schema: The “contract” that defines types, fields, queries, and mutations.

- Query: Read-only operation to fetch data.

- Mutation: Operation that changes data (create, update, delete).

- Resolver: Server-side function that fetches data for a field.

Phase 1: GraphQL Endpoint Discovery and Reconnaissance

You cannot test what you cannot find. GraphQL endpoints are not always obvious, and they are not always placed at /graphql.

Common endpoint patterns to try

Start with predictable locations such as:

/graphql/api/graphql/v1/graphql/api/<app-name>/graphql

Analyzing Network Traffic for GraphQL Queries

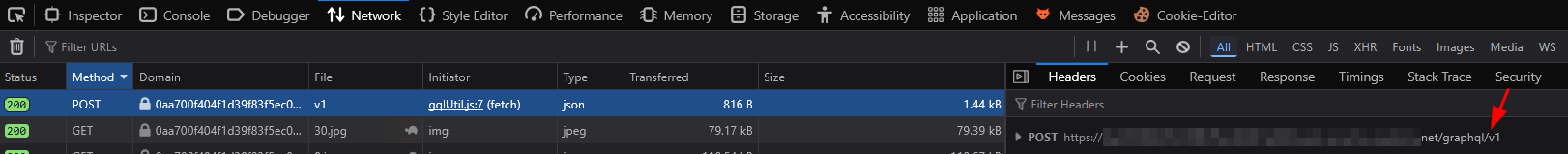

If the target is a web app, open Developer Tools:

- Go to F12 → Network

- Filter for POST requests

- Look for requests that include a

queryparameter or a request body containingquery,operationName, andvariables

GraphQL usage tends to be noisy in network logs because many apps rely on it heavily.

A common real-world obstacle is that the endpoint is not obvious in traffic until specific screens load. If the endpoint isn't visible in traffic, check the client-side code.

- Manual Search: Inspect JavaScript bundles for keywords like

/graphql,operationName,Apollo, orrelayto find hardcoded paths. - Automated Scan: Use the InQL Burp Suite extension. It automatically identifies GraphQL endpoints within your target and can even reconstruct schema definitions directly from the analysis.

Phase 2: GraphQL Introspection Vulnerability

Introspection is a built-in GraphQL feature that allows clients to query the API about itself. Developers use it for tooling and documentation, but leaving it enabled in production can leak a complete blueprint of the backend.

If enabled, introspection can reveal:

- Types and relationships

- Queries and mutations

- Field names and arguments

- Sometimes internal or “private” fields that should never be discoverable

A simple introspection payload

A minimal example looks like this:

{ __schema { types { name fields { name } } } }

Even this basic query can provide enough structure to start building targeted attacks.

Visualizing GraphQL Schemas for Security Analysis

Introspection responses can be large and hard to reason about in raw JSON. Two common approaches to visualize the schema are:

- GraphQL Voyager (graph-based visualization)

- InQL (Burp Suite extension that helps explore and attack GraphQL)

Some teams disable introspection in production, but still accidentally expose sensitive fields in the schema definition itself, such as:

isAdmininternal_id- other flags, roles, or back-office identifiers

Even if you cannot run full introspection, leaked field names from documentation, client code, or error messages can still allow attackers to craft dangerous queries.

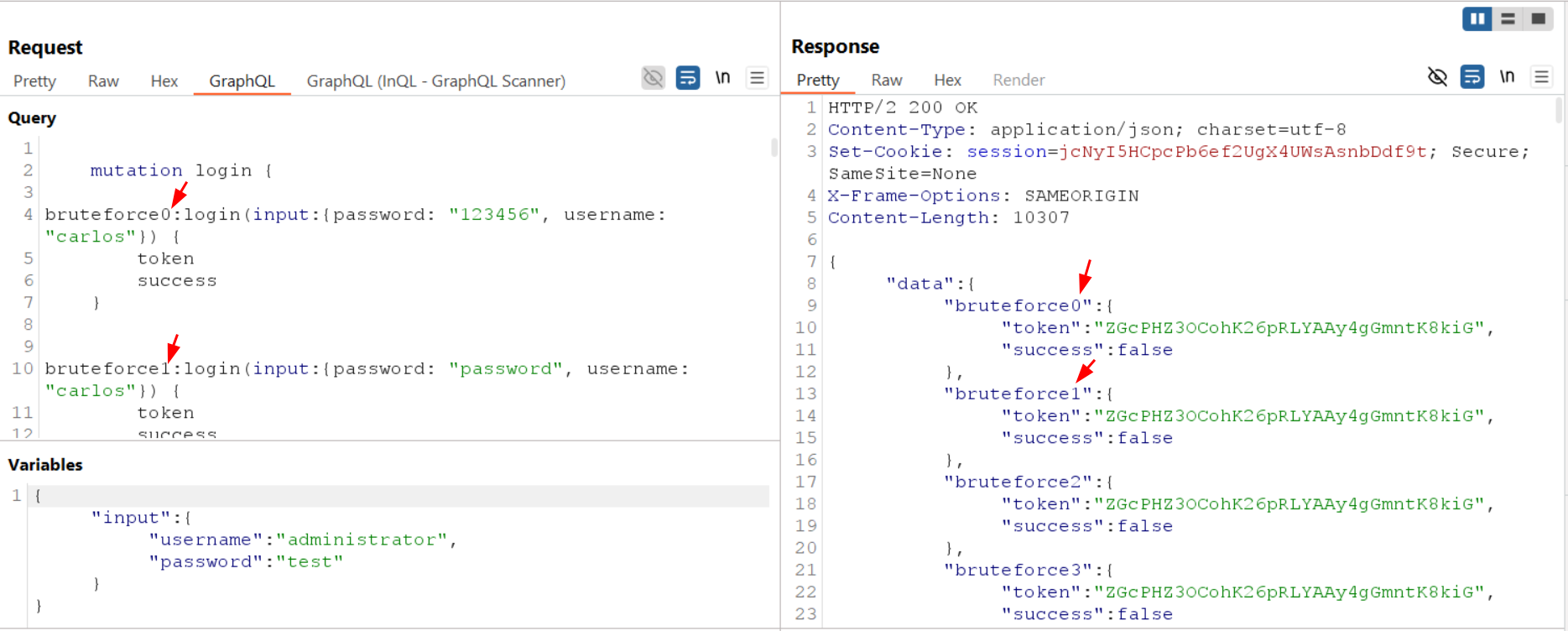

Phase 3: GraphQL Batching Attack (Bypassing Rate Limits)

A lot of defenses are designed around HTTP, not GraphQL. Traditional rate limiters often count “requests per minute,” but a single GraphQL request can carry multiple operations.

GraphQL supports sending multiple operations in one request through:

- Batching (an array of queries in one POST, depending on server support)

- Aliases, which allow the same resolver to be invoked many times under different names

The result: you might execute 100 logical attempts while the perimeter sees only one HTTP request.

Example: brute forcing a PIN with aliases

Instead of sending many requests (and hitting a block), an attacker can attempt many logins inside a single mutation:

mutation {

try1: login(input: {pin: 1111})

try2: login(input: {pin: 1112})

...

try100: login(input: {pin: 1211})

}

In a typical lab pattern:

- Several failed logins cause a temporary ban or WAF rule.

- Batching compresses many attempts into one request.

- The protection does not trigger because it is measuring HTTP traffic, not operation count.

Phase 4: The GraphQL N+1 Problem (Database Exhaustion)

The N+1 problem is not always treated as a “security bug,” but it becomes one when it can be weaponized for denial of service.

It happens when:

- A resolver fetches a list (1 query)

- For each item in that list, another resolver fetches related data (N queries)

Example logic:

SELECT * FROM Authors LIMIT 100SELECT * FROM Posts WHERE author_id = ?(run 100 times)

Total: 101 database calls from a single GraphQL request.

A practical attack approach

Attackers look for queries where nesting multiplies backend work:

query {

users(first: 1000) { # 1 DB call (or a few)

friends { # 1000 DB calls

posts { # 1000 * 50 DB calls (example)

comments # potentially explodes further

}

}

}

}

Impact

This can cause:

- CPU spikes

- DB connection pool exhaustion

- lock contention

- full application downtime

And because it is “one request,” it can bypass simplistic rate limiting.

Phase 5: Query Depth Limit Bypass

Many GraphQL servers defend against abusive queries by limiting depth, meaning the maximum allowed nesting level.

That is a good baseline, but it is not sufficient on its own.

Implementing Query Depth Limiting

Example rule: “Block queries deeper than 5 levels.”

This helps against obvious recursive nesting, but attackers can still generate extreme cost without deep nesting.

Exploiting Recursive Relationships and Circular Queries

GraphQL schemas often have relationships that loop naturally, such as:

- User → Posts → Author → Posts → Author → …

Example idea:

query {

user {

posts {

author {

posts {

author { ... } # repeat until the server breaks

}

}

}

}

}

Bypassing Depth Limits using Query Width and Aliases

Even with depth controls, an attacker can:

- request many fields at the same level (width)

- use aliases to repeat the same expensive resolver multiple times

In other words, a query can stay shallow but still be computationally huge.

Phase 6: Broken Access Control and CSRF Over GraphQL

GraphQL does not automatically solve authorization. Access control still must be enforced in resolvers, and mistakes can become systemic because one schema often backs many clients.

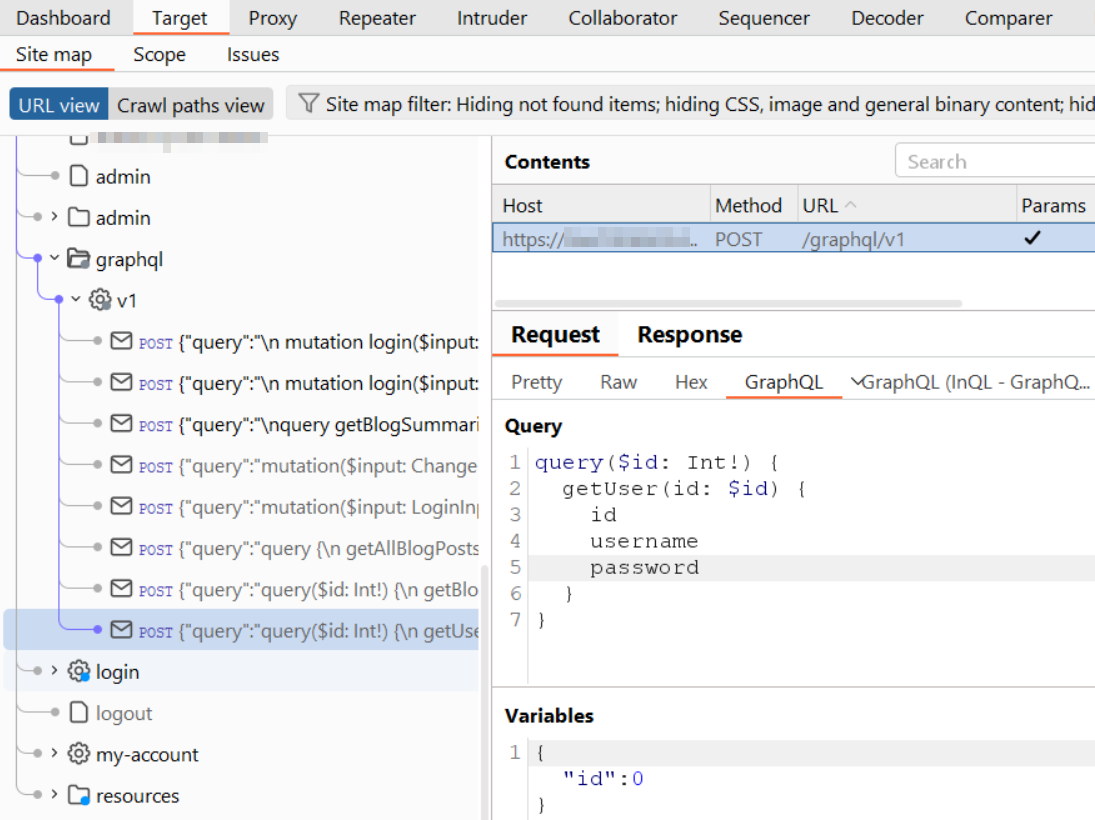

Broken access control in resolvers

A common flaw is an IDOR-style pattern:

- A resolver checks that a resource exists.

- It does not check that the requester owns it or is allowed to view it.

Example:

- The request includes

id: 5. - Changing it to

id: 6returns another user’s private data.

This is especially common when the schema makes it easy to query by IDs and when authorization logic is inconsistent across resolvers.

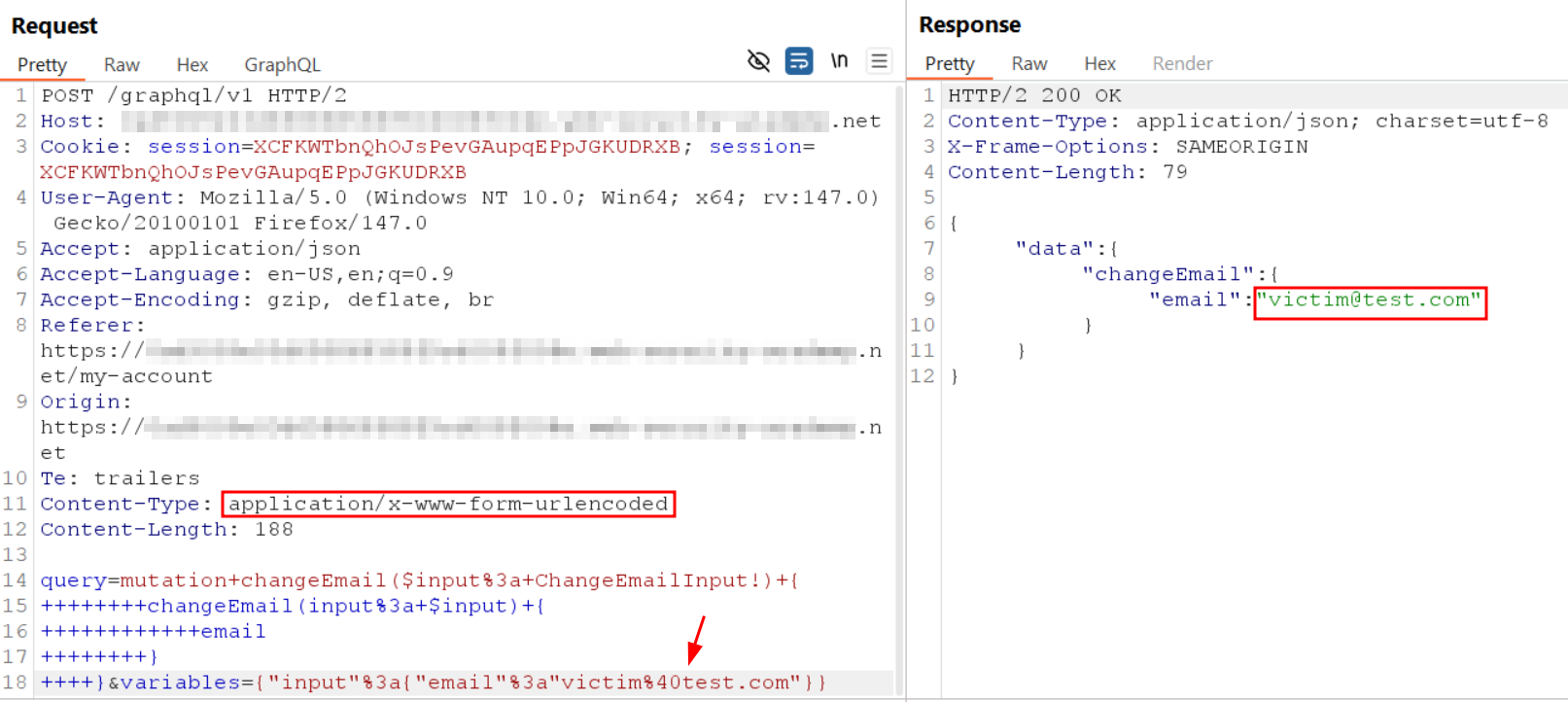

CSRF over GraphQL

Many teams assume “GraphQL is JSON over POST, so CSRF is not relevant.” That assumption can fail if the endpoint accepts alternative content types or methods.

If the endpoint allows:

GETrequests, orapplication/x-www-form-urlencoded

then a victim can be tricked into executing a mutation (for example, changing an email address) just by visiting a malicious page while authenticated.

Remediation

A strong GraphQL security posture is usually a layered set of controls, not a single fix.

Disable introspection in production

Keep introspection enabled in development, but restrict it in production environments. If you must keep it, allow it only for trusted roles or admin tooling.

Enforce query cost analysis (not only depth)

Depth limits help, but cost-based controls are harder to bypass. Assign “cost points” to expensive fields and block queries whose total cost exceeds a threshold.

Fix N+1 with batching patterns (example: DataLoader)

On the backend, use batching libraries (such as DataLoader) to ensure that resolvers fetch related data efficiently rather than running one query per item.

Rate limit by GraphQL operations and complexity

Do not rely only on “requests per minute.” Track:

- number of operations per request

- query complexity score

- resolver execution time patterns

This makes batching attacks far less effective.

How Jsmon Can Help in Real Assessments

When GraphQL endpoints and schema details are hidden, client-side JavaScript becomes a valuable source of truth. This is where Jsmon fits naturally into a recon workflow.

Hidden discovery from JavaScript bundles

Jsmon can scan JavaScript assets to extract hardcoded GraphQL endpoints that may not appear immediately in normal browsing flows.

Schema reconstruction without introspection

Even if introspection is disabled, Jsmon can pull field names, query structures, and mutation patterns from client code. That allows you to build valid queries “blind,” which is often enough to test access control, batching behavior, and expensive resolvers.

Conclusion

GraphQL is powerful, but it changes the security model. The client is no longer just consuming data. The client is describing workloads, exploring relationships, and indirectly influencing backend behavior.

A thorough GraphQL security review typically follows a clear path:

- Find the endpoint (discovery).

- Understand the schema (introspection or reconstruction).

- Abuse operational flexibility (batching and aliases).

- Stress backend design flaws (N+1 and depth/complexity bypasses).

- Validate authorization and request integrity (access control and CSRF).

The most important mindset shift is simple: test GraphQL like a graph, not like a list of endpoints.