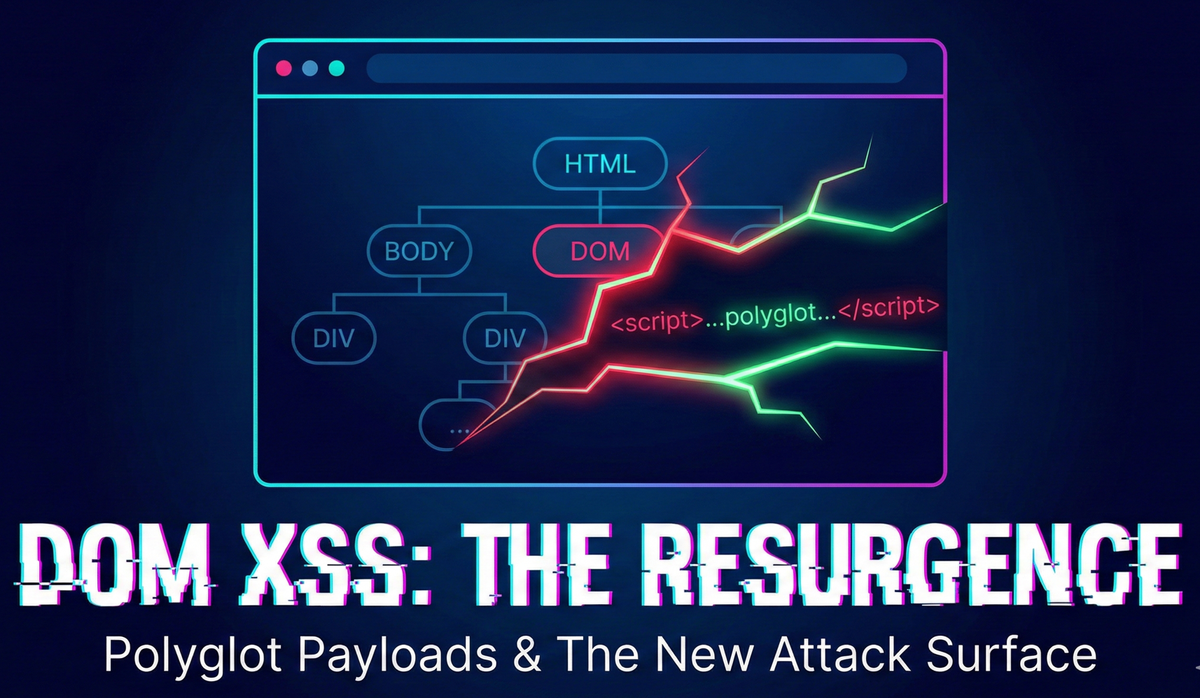

DOM XSS Is Not Dead: The Rise of Polyglot Payloads

Today, attackers increasingly focus on: DOM-based XSS, where the vulnerability exists in client-side JavaScript logic. Blind XSS, where payloads execute in backend admin panels or internal tools, often out of sight.

Modern web security tooling has significantly reduced the impact of traditional reflected XSS. Simple payloads like ?q=<script>alert(1)</script> are now routinely blocked by frameworks such as React or Vue, Content Security Policies, and web application firewalls (WAFs).

However, this does not mean cross-site scripting is gone. Instead, the battleground has shifted. Today, attackers increasingly focus on:

- DOM-based XSS, where the vulnerability exists in client-side JavaScript logic.

- Blind XSS, where payloads execute in backend admin panels or internal tools, often out of sight.

In these scenarios, the main challenge is uncertainty: the attacker does not always know exactly where user-controlled data will end up. It might appear in an HTML attribute, a JavaScript string, a meta tag, or a JSON object.

This is where XSS polyglots come in: carefully crafted payloads that can adapt to multiple contexts at once.

The Modern XSS Landscape

Why Traditional Reflected XSS Is Fading

Historically, reflected XSS depended on injecting a malicious payload into a request parameter, which the server later reflected in the response without proper sanitization. For example:

[<https://target.com/?search=><script>alert(1)</script>](<https://target.com/?search=><script>alert(1)</script>)

In modern architectures, this attack faces several obstacles:

- WAFs inspect inbound requests and block obvious XSS signatures before they reach the application.

- Front-end frameworks often escape or sanitize user input by default.

- Browser protections and secure defaults reduce the likelihood of naive script injection succeeding.

The result is that old-school reflected XSS is far less common in well-defended applications.

DOM XSS and the WAF Blind Spot

DOM-based XSS is different. Here, the dangerous flow, from source (user input) to sink (a sensitive DOM API), happens entirely inside the browser. The payload may never be visible to a server-side WAF at all.

Consider a payload placed in the URL fragment:

<https://target.com/#><img src=x onerror=alert(1)>- Everything after

#is a fragment identifier. - Browsers do not send the fragment to the server.

- The WAF only sees something like:

GET / HTTP/1.1with no evidence of<img src=x onerror=alert(1)>.

If the page’s JavaScript does this:

// Vulnerable DOM logic

var userHash = window.location.hash; // Reads attacker-controlled data

document.getElementById('header').innerHTML = userHash; // Inserts it as HTMLThe malicious fragment is now rendered directly into the DOM. The WAF cannot help because the payload never crossed the network boundary in a form it could inspect.

This is the “WAF gap”: server-side protections cannot see or control purely client-side execution paths.

How WAFs Try To Stop XSS (And Where They Fall Short)

1. Signature-Based Detection

Most WAFs maintain a library of patterns commonly associated with XSS, such as:

- HTML tags:

<script>,<iframe>,<img>,<svg> - Event handlers:

onerror,onload,onmouseover, and others - Dangerous keywords:

alert(),prompt(),document.cookie

If a request contains these patterns in a suspicious context, the WAF can block it immediately.

2. Normalization and Decoding

Attackers rarely send raw payloads anymore. They rely on encoding tricks like:

- URL encoding (

%3Cscript%3E) - HTML entities (

<script>) - Hex or Base64 schemes

To counter this, WAFs normalize input first. For example:

<is decoded back to<- Encoded sequences in query parameters are converted to their raw form

This allows the WAF to detect hidden script tags or attributes even when they are obfuscated.

3. Heuristic and Behavioral Analysis

Modern WAFs also look beyond simple string patterns. They analyze behavior and context, such as:

- Context inspection: Is user input being placed inside an HTML tag, a JavaScript string, or a URL parameter where code execution is possible?

- Anomaly detection: Does this request contain unusual characters, malformed structures, or patterns that deviate from normal traffic for this endpoint?

This heuristic approach helps catch novel payloads that do not match any known signature.

4. Rules-Based Input Validation

Some WAFs act as an additional validation layer:

- Enforcing strict rules on what input is allowed.

- Rejecting any value that does not match expected formats (for example, a phone number field containing letters, quotes, or angle brackets).

This reduces the attack surface, especially on parameters that should never contain HTML or JavaScript.

5. Advanced Techniques

To push detection further, WAFs may combine:

- Complex regular expressions to spot obfuscated payloads.

- Machine learning models trained on real-world traffic to detect suspicious patterns.

Even with these capabilities, there is a fundamental limitation: WAFs operate on network traffic, not on what happens inside the browser. DOM-based XSS remains largely outside their visibility.

Trusted Types: Hardening the Browser Against DOM XSS

While WAFs defend at the perimeter, Trusted Types move the defense closer to where DOM XSS actually occurs: the browser itself.

What Trusted Types Do

Trusted Types prevent unsafe data from reaching dangerous DOM APIs by enforcing a strict policy:

- Certain DOM sinks, such as

innerHTML,document.write(), or dynamic script creation, are treated as injection points. - Instead of accepting arbitrary strings, these sinks are configured to only accept special Trusted Types objects.

- Raw, unvalidated strings are rejected. If code attempts to assign them, the browser throws a

TypeErrorand blocks the operation.

How Trusted Types Are Enabled

- Identify injection sinks The browser recognizes APIs that frequently lead to XSS if misused, such as:

element.innerHTML, eval(), document.write() - Enforce via Content Security Policy Trusted Types are activated through CSP headers. When enforced, these sinks will reject unsafe strings by default.

- Define Trusted Types policies Developers write policies that:

- Sanitize HTML using libraries like DomPurify.

- Control or restrict script URLs and dynamic script execution.

- Generate Trusted objects Instead of returning plain strings, these policies produce: Only these safe objects are allowed into sensitive sinks-

TrustedHTML, TrustedScript, TrustedScriptURL - Secure injection paths Application code must route any user-controlled content through a Trusted Types policy before inserting it into the DOM, reducing the chance of accidental DOM XSS.

Trusted Types do not eliminate the need for input validation or output encoding, but they substantially raise the bar for exploiting DOM-based vulnerabilities.

Exploitation in Practice: Why Polyglots Matter

The Problem: Unknown Context

In real-world applications, user-controlled data can surface in many places on the same page:

- As part of an HTML attribute

- Embedded inside a

<script>block - Included in inline style or

<style>tags - Injected into textarea, title, or meta tags

- Used inside regular expressions or JavaScript strings

If you know the exact context, you can craft a minimal, specialized payload. But when the context is uncertain, or varies across different injection points, you need something more flexible.

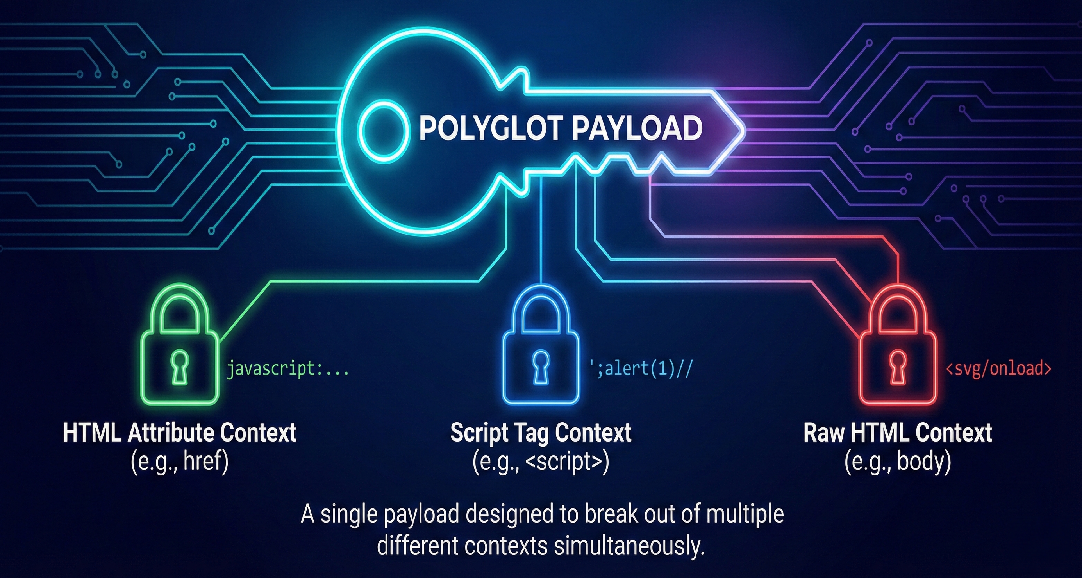

What Is an XSS Polyglot?

In the XSS world, a polyglot is a single payload designed to function across multiple syntactic contexts.

A simplified analogy:

- A normal payload is a key cut for one specific lock.

- A polyglot is a skeleton key. It carries the right shapes and characters to escape many different “locks” at once: HTML, JavaScript, URL, or regex contexts.

Examples of context-specific behavior:

- Inside an HTML attribute: you may need to break out of

"and inject a new attribute or tag. - Inside a script block: you may need to close a string, terminate a statement with

;, and then run arbitrary JavaScript. - Inside a URL: you might rely on the

javascript:protocol to trigger execution when a link is clicked.

A polyglot payload combines these tricks into a single string.

Why Polyglots Are Useful

Web applications have become more complex, and the same piece of user-controlled data might be:

- Stored once.

- Reflected in multiple places in the DOM.

- Transformed or encoded before rendering.

A polyglot payload increases the chance that at least one of those reflection points is vulnerable in a way that leads to execution.

Real-World Polyglot Examples

Example 1: Multi-Context Polyglot

javascript://%250Aalert(1)//"/*\\\\'/*"/*--></script><svg/onload=alert(1)>What it tries to achieve:

javascript:Acts as a protocol handler in URL contexts likehref. If interpreted as a URL, the browser treats the rest as JavaScript.//Starts a comment in JavaScript, ensuring that any trailing text does not cause syntax errors.- Encoded newline:

%250ACan influence how some filters normalize or process the payload. ->and</script>Help break out of HTML comments or script blocks if the payload is inserted there.<svg/onload=alert(1)>Acts as a pure HTML-based trigger if the payload ends up directly in the HTML body. Theonloadhandler callsalert(1)when the element is parsed.

Together, these elements allow the payload to function whether it lands in an attribute, a script tag, or raw HTML.

Example 2: Complex Polyglot for HTML, URL, and JavaScript Contexts

jaVasCript:/*-/*`/*\\\\ `/*'/*"/%0D%0A

%0d%0a*/(/* */oNcliCk=alert() )//</stYle/

</titLe/</teXtarEa/</scRipt/-->\\\\x3c

iframe/<iframe/oNIoAd=alert()//>\\\\x3e

1. HTML Context

If this is inserted directly into the HTML body, the browser scans until it encounters a valid HTML tag:

- Eventually it sees

<iframe/. - The attribute

oNIoAd=alert()(case-insensitiveonload) becomes an event handler. - When the iframe loads,

alert()is executed. //comments out anything that follows, helping to avoid syntax issues.

The browser automatically closes the <iframe> element, completing the tag.

2. URL / href Context

If placed inside an anchor tag:

<a href="jaVasCript:/*-/*`/*\\\\ `/*'/*"/%0D%0A ...">jaVasCript:Triggers JavaScript execution when the user activates the link.- Mixed capitalization can bypass simplistic filters that only look for

javascript:in lowercase. /*-/*and other comment patterns are there to:- Neutralize parts of the payload as comments in certain parsing scenarios.

- Allow the browser to eventually reach meaningful JavaScript like

(/* */oNcliCk=alert() ).

//again comments out anything after the main code.

3. JavaScript Regular Expression Context

If the payload is improperly inserted into a regex literal, for example:

var regex = /USER_INPUT/;

When USER_INPUT is replaced with the polyglot:

- The first

/in the payload can close the regular expression. - Operators like and are treated as arithmetic on invalid operands, resulting in

NaNbut not necessarily a hard error. - Comment blocks

/* ... */neutralize sections. - The critical part is

(oNcliCk=alert()):- Wrapped in parentheses, it is evaluated as a standalone expression.

- The assignment causes

alert()to run. - Without these parentheses, JavaScript might try to treat the preceding expression as part of the assignment and fail.

This design lets the same payload survive very different parsing rules and still produce execution in at least one context.

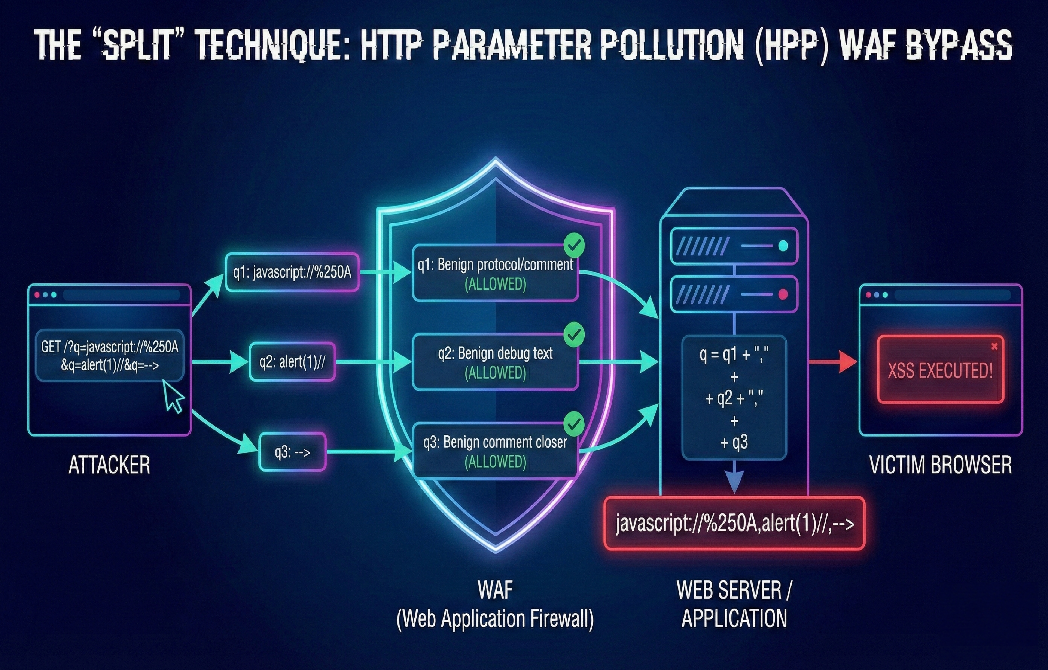

Technical Deep Dive: The “Split” Technique

The Problem

Modern WAFs are very effective at spotting long, clearly malicious sequences such as: <svg/onload=alert(1)>

A continuous payload like this is easy to fingerprint. It contains multiple high‑risk patterns in one place, so signature and heuristic engines quickly flag and block it.

The Idea: Split the Payload with HTTP Parameter Pollution (HPP)

Instead of sending one large, suspicious-looking payload, the attacker can split it across multiple parameters using HTTP Parameter Pollution (HPP). For example:

?q=javascript://%250A&q=alert(1)//&q=-->

Each q parameter on its own appears relatively harmless:

javascript://%250Alooks like a URL or protocol test.alert(1)//resembles a debug fragment or inline comment.-->can pass as a stray HTML comment closer.

No single parameter carries the full malicious intent.

Why This Works

- Bypassing WAF Inspection Many WAF configurations inspect each parameter in isolation. When the payload is broken into smaller chunks: Because none of these fragments looks dangerous on its own, the WAF allows them through.

javascript://%250Adoes not match a complete XSS signature.alert(1)//is often treated as a benign snippet.-->is common in HTML comment handling.- Concatenate them into a single value.

- Sometimes use separators such as commas during the join.

- Polyglot Logic and Comment Abuse The trick is in how the chunks are crafted: When this reconstructed value is finally injected into a vulnerable sink (for example,

innerHTML, a script block, or ajavascript:URL), the browser interprets it as a single, valid payload. The code executes as intended, even though no single request parameter looked obviously malicious at the WAF layer.- Each fragment is designed so that any join characters inserted by the backend (for example, commas) are safely neutralized.

- By ending a piece with

//, the attacker turns the rest of the line into a JavaScript comment. - As a result, separators introduced during concatenation are ignored by the browser’s JavaScript engine.

Backend Reassembly via Duplicate Parameters On the server side, certain frameworks and platforms (for example, some ASP.NET or Node.js setups) accept duplicate parameters and then: The application might end up with something roughly equivalent to:

javascript://%250A,alert(1)//,-->

Even though the WAF only saw harmless pieces, the application now holds a reconstructed payload that is far more dangerous.

Impact of DOM XSS and Polyglots

DOM-based XSS combined with polyglot payloads can lead to serious consequences:

- Account compromise Stealing session tokens, local storage, or other sensitive identifiers.

- Privilege escalation Executing actions as the victim user in high-privilege interfaces such as admin panels.

- Data exfiltration Extracting personal data, internal records, or API responses visible only to the victim’s browser.

- Supply-chain style abuse Injecting malicious logic into third-party widgets, analytics dashboards, or embedded admin consoles.

Because some of these attacks occur in back-office or internal environments (for example, when an admin views a malicious support ticket), they may remain undetected for longer and affect highly sensitive systems.

Conclusion

Reflected XSS may be less common today, but DOM-based XSS remains very much alive, often thriving in areas that traditional WAF protections cannot see. As applications rely more heavily on complex front-end logic, user-controlled data travels through many layers of JavaScript before it appears in the DOM.

In this environment:

- WAFs and basic filters are necessary but not sufficient.

- Browser-level defenses such as Trusted Types provide a powerful safety net around known injection sinks.

- Polyglot payloads illustrate how attackers adapt, designing single payloads that can exploit multiple contexts at once, especially when they lack full visibility into how their input is used.

For defenders, the path forward is clear:

- Treat DOM XSS with the same seriousness as server-side XSS.

- Audit client-side code for dangerous data flows.

- Combine server-side controls, browser security features, and careful coding practices.

DOM XSS is not dead. It has simply moved closer to the user’s browser, and demands equally modern defenses to keep it in check.